No-trade deal

This time last year we stood a week from Budget 2020 and all the talk was about preparing for a ‘once in a lifetime’ economic event - Brexit. We have all lived a second lifetime since then, but the end of the Brexit transition is still a monumental event for Ireland. Our nearest neighbour leaving the EU will have political, social, and economic ramifications which are long-lasting and far-reaching for this island. In this piece, however, I am going to indulge in a little parochialism by addressing what the Government can do in next week’s Budget to help prepare for Brexit.

If the worst-case scenario occurs, it will fundamentally reframe the economic outlook for both the country and the region’s most reliant on Brexit exposed sectors. Whilst some parts of the country may begin to recover from COVID in 2021, others would be sent in a second recessionary spiral - one with long-lasting impacts on their economic structure and productivity.

Even in a ‘bare bones’ FTA scenario, there would be significant additional costs for Irish companies arising from additional customs procedures, regulatory burdens, and rising transport costs. Additional paperwork, certification and delays in trade would gradually erode the efficiency of interlinked supply chains, both with the UK and through the landbridge to the continent. This would add extra costs at each step of production and distribution.

How big is Brexit

It is not unusual to see commentary that points out that only a little over one-tenth of Irish goods exports go to the UK in any given year. So surely the blow won’t be that big? This, unfortunately, ignores the kind of asymmetries which dominate Irish economic data. The sectors reliant on UK trade are a quite small share of exports but they dominate the linkages of those exports back into cashflow to the domestic economy.

Take for example the Irish food and drink sector. The sector is by far the most exposed of any sector in any country in Europe to a no trade deal Brexit – at 37% UK export share. If you take all the food and drink products in all the EU Member States, Irish food and drink products account for seven of the ten most Brexit exposed.

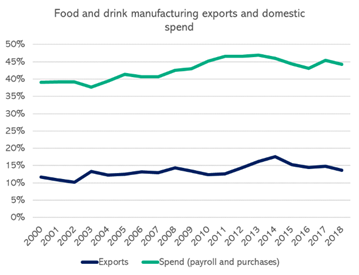

Of the €151 billion of Irish goods exports in 2019, only 9% was food and drink exports. But over the past decade, the sector has spent over €120 billion in payroll and purchases in the Irish economy. Whilst only accounting for one-tenth of manufactured exports, it accounted for 45% of the total spend of all manufacturers in the domestic economy. €82 billion of this amount was purchases of materials from primary producers and other domestic firms in their supply chain. This makes the food and drink sector by far the largest purchaser of goods and services in the Irish economy of any sector outside retail.

Source: Ibec analysis of ABSEI data

Falling demand due to a no-trade deal end to transition would flow down the supply chain in the form of reduced demand for intermediate goods and services off suppliers, as well as reduced demand for product from primary producers. This in turn would depress prices for those producers.

The first-order effects of a fall in food and drink exports might not move the dial on Irish GDP massively, but the second-order impacts on employment, incomes, and supply chains would be significant.

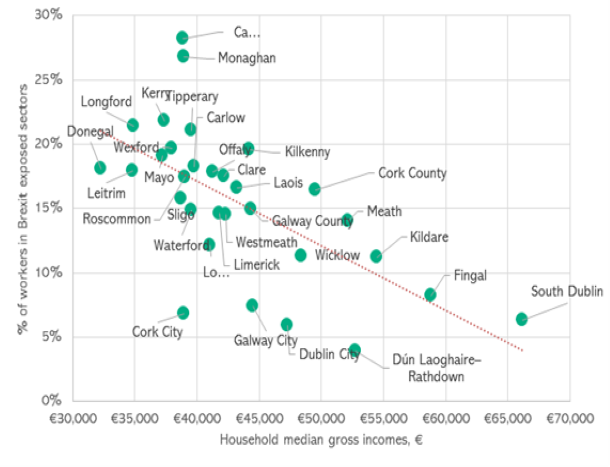

The impact of a no-trade deal outcome would not impact all the country evenly either. It is an unfortunate reality that most Brexit-exposed sectors are concentrated in the poorest parts of the country. We can see below – there is a direct correlation between the average income in a county and how exposed it is to the prospect of a no-deal Brexit.

Source: Ibec analysis

What can be done in Budget 2021?

How it is funded

Ultimately a no-trade deal Brexit will require Irish companies to find new markets for their product. There are reasons why the UK has always been attractive for Irish producers – it is a large, close market, with a shared retail footprint and similar tastes. Building new markets, on the other hand, involves considerable risk and expense. Even within the single market companies face risks in establishing commercial relationships and supply-chains.

Also, they must build cash-flow, hold more inventory, innovate, and invest to tailor the product to consumer tastes and deal with new regulatory regimes. The further goods travel the tighter margins will be, as transport costs increase.

Time is also against companies. Loss of UK market share, where it occurs, is likely to happen relatively quickly, whilst replacing lost food exports would take years. Significant resources will be needed to help companies meet these conjoined challenges of buying time to adjust and building new markets.

The Government has already committed to this challenge with €5 billion in funding to be set aside in a Brexit contingency fund between 2020 and 2025. In addition, we will find out how the EU’s €5 billion Brexit adjustment fund will be dispersed in November. Finally, tariffs on Irish imports from the UK will amount to about €1.5 billion annually of which one-quarter will be kept by the Irish exchequer. All these resources will need to be recycled into the supports for the worst-hit sectors and regions over the coming years.

How it is spent

Firstly, given their capital intensive nature and their low margin nature, these businesses can take decades to build and are very vulnerable to changing external conditions. If emergency supports are not in place early and firms close their doors there will be little hope of resuscitating the industrial base of many rural areas in the medium-term. Any major response will need to follow our response to COVID and introduce emergency payroll supports, by extending the Employee Wage Subsidy Scheme to Brexit impacted business.

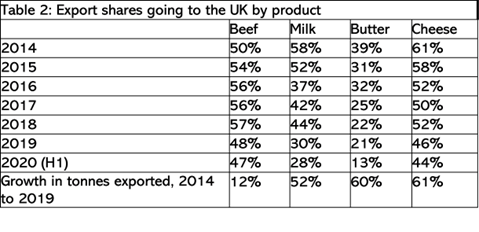

Secondly, there has been a significant focus in recent years on accelerating the pace of diversification of exports to new markets. This is not an easy task. Recent analysis, in our Q2 economic outlook, has shown some success in the food and drink sector. The value share of food and drink exports going to the UK has fallen from 44% in 2015 to 35% in the first half of this year. But this has been driven almost solely by a massive investment by dairy companies. On the other hand, progress in diversifying sectors like beef, drink, forestry, and fresh produce has been much slower.

Sectors, where we have globally scaled firms in the supply chain, value-add products, greater margins & have climate/shelf-life in their favour, are diversifying. In others, their non-UK market potential is limited due to shelf life, climatic differences, and market preferences. Unfortunately, the lagging sectors account for around 75% of the manufacturing jobs.

Building ongoing new markets will need intensive long-term investments in enabling infrastructure, technology, customs training, plant renewal and expansion, market development, trade promotion and innovation. Companies have spent hundreds of millions on this since 2016, but ongoing State support will be needed.

Finally, and urgently, firms are being asked to grow into new markets at a rapid pace but are doing so at considerable risk. Most companies buy trade credit insurance to help mitigate those risks when building new markets. But unfortunately, supply in that market, which collapsed during the global financial crisis, is contracting rapidly again.

Ireland is one of a handful of countries in the EU that does not offer some form of State support for export credit insurance. This means firms entering contracts with buyers or suppliers aboard are being priced out of insurance or being denied it altogether. The Irish State must introduce a supported export credit insurance scheme to ensure the gap in the supply of export credit insurance does not impact on the ability of firms to prepare for Brexit.